Wilderness. Vast. Desert-dwelling. Words like these crept into my imagination like incantations and gave seed to a secret reel of epic imagery that spooled through my mind as I sat dumbly at my office desk. I saw endless swathes of yellow and gold beneath a blinding sky. I saw an undulating sea of red sand that swallowed up all living things and offered nothing in return but a shimmering haze of heat. I saw strings of lean, surefooted Oryx descending towering dunes, sitting back on their haunches as they sunk knee-deep into the loose, warm sand. Amidst all of this I saw a small and insignificant human figure, dwindling into the distance, dwarfed by the enormity and emptiness of the Namibian landscape. Me.

I was one of a group of nine fundraisers who had campaigned for sponsorship to undertake a week-long trek through Damaraland, a remote and virtually untouched area in the northwestern corner of the Namib Desert. The funds would go to the Elephant-Human Relations Aid (*EHRA), an organisation working to protect the small population of astonishing and rare desert-dwelling elephants of the area. Though I’d never set foot in the desert country before, the idea of abandoning my current life for seven days spent wandering through vast tracts of uninhabited wilderness pulled at me with all the promise of a holy pilgrimage to a sacred and powerful land.

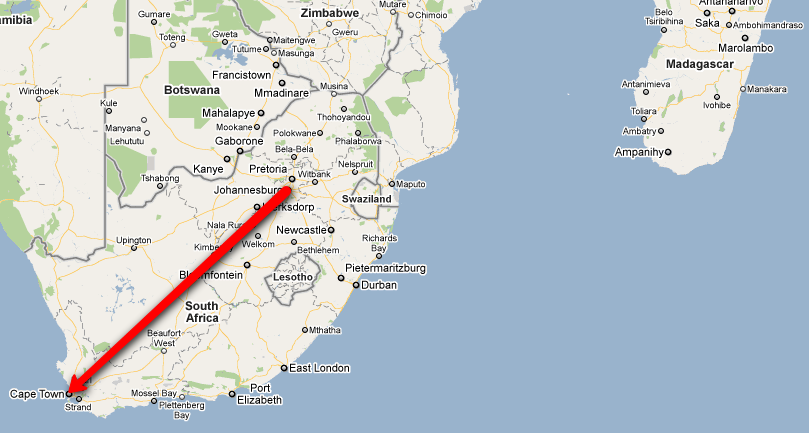

After months of agonised waiting, the date of my departure finally arrived and I boarded a plane bound for Swakopmund. On a warm September morning, we began our trek at the foot of the Brandberg Mountain, so called for the fiery red that bathes its slopes in the light of the setting sun. With that majestic landmark at our backs, we set off into a world – and a way of being – that outdid even my most fantastic desk-bound daydreams.

On the first morning, I woke before dawn to a royal blue sky still studded with the sparks of the night’s dwindling stars. Sleepy silhouettes ringed the cook fire, silently watching the coffee kettle as it came to boil. As we warmed our hands around our tin mugs, the dawn began to show itself in a flushed pastel palette that bled from the sky to paint the chilled earth in ever-warming shades.

At that early hour, the desert had a profound stillness about it. It was as though the land held its breath, drawing out the last few moments of cool before the brutal heat of the day took hold and the daily struggle of survival in the desert commenced.

We quickly came to learn that when you move through the desert on foot, clues narrating this constant struggle become clear. The animals’ stories were written out across the sand in the subtle language of tracks and spoor; riddles that hinted at the grand drama of life playing out all around us. Narrow game tracks crisscrossed our path like vapour trails, though the animals themselves were harder to find.

Only an hour’s walk from our first camp we came upon leopard tracks and a freshly excavated scrape; a territorial marking where the dirt had been kicked up and sprayed with urine. We were thrilled and unsettled to think that not far from where we lay sleeping beside the dying embers of our fire, a leopard wove warily through the night, the unfamiliar scent of man and wood smoke on her nose. How alien and oblivious we really were in that wild place.

Damaraland is a varied landscape and a geologist’s wildest dream. Sometimes the walking was easy as we strolled comfortably over flat, hard ground while shy, willowy giraffe loped through scantily clad trees before us. Sometimes the going was tough and we poured rich, red sand from our shoes at every water break. One morning we walked through a fog so thick it looked like snowflakes falling through our torch beams. Later it burnt off to reveal a pebbled moonscape fringed by tall, jagged crags. We studied rocks baring the mosaic marks of ancient caked mud, inspected the inner galaxies of split geodes and polished crystals of glittering quartz with our sleeves.

On the third day we climbed the slopes of Doros Crater, picking our way over large, loose rocks that tumbled down behind us. We topped the crater rim and stared out at the immense plain unfolding below. Far from dull, the desert flaunted a heart-stopping spectrum of gold, toffee, caramel and coffee. In the impossible distance, copper-sloped cliffs crowded the horizon. Ant-like, we spied the minute semi-circle of our support vehicles waiting to meet us at our rendezvous co-ordinates below.

As we sat and marvelled silently at the sheer expanse of uninhabited space all around, our radio roared to life and a distorted version of Frank Sinatra’s Fly Me to the Moon warbled weirdly from the speaker. Our support convoy was transmitting the song to us as it played in one of the cars below. The bizarre sound was jarringly out of place in the remote wilderness, though the sentiment seemed apt as we gazed out over the otherworldly scene laid out before us.

Inevitably, 122km and seven days of life in this beautiful place came to an end. I picked a window seat on the plane and as I passed over the creased red earth of my Mecca my heart sunk at the prospect of my waiting desk. At least, I thought, I’ll have more than just my imagination to comfort me. This time, I’ll have memories.

Memories of the thin, eerie cries of jackals stealing softly through the night. Of the dazzling sight of the sun glinting off the striped flanks of a herd of zebra as they trickle down a distant slope. Of bedding down beneath a bottomless sky overrun by an army of brilliant stars. Of endless vistas of ochre and rust. And above all, of the exquisite sense of peace that descended upon each of us as we walked deeper into that magical, sprawling wilderness.

*For more information on EHRA and their conservation work in Namibia, go to www.desertelephant.org.

All words and images by Leanne Farish.